- Home

- Robin Wasserman

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Page 12

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Read online

Page 12

It only occurred to me once he was gone. Aphantasia, an inability to conjure what one wished. Other people could wish whatever faces they wanted to see again. The wife across the street, if her husband left her, if her baby turned blue, she could close her eyes, will their faces to mind, pretend them back to her. Everyone I knew, everyone I passed on the street, the teeming mass of humanity, could accomplish a miracle. When I closed my eyes, willed my brain, Benjamin, Benjamin, Benjamin, he never appeared.

* * *

I came home from the Meadowlark to find a message from Nina on the answering machine, and resisted the impulse to ignore it. “I got the transfer,” she said when I called back. “Thank you.” Every call I made to Nina felt like the call I’d made that morning, the call to say your father is dead.

Each month I deposited money into her account, as Benjamin had before. And each month she called to say a begrudging thanks and make perfunctory inquiries into my physical and emotional welfare. I told her I was glad she called. She said she was glad to hear from me. We were both, as always, very polite. We left it that we would have dinner together sometime. Talk more, and more in depth, someday. This was where our relationship thrived: an ambiguous future that would never come.

After I’d showered off the stink of the past, or at least lathered it over with lavender bath gel and half a tablet from the emergency Xanax stash, I suggested to Alice that we order a pizza. She wasn’t my child, so there seemed no reason not to share the wine. She picked all the pepperonis off her slice, stacking them in a neat, greasy tower. “I read your book.”

“Should I ask what you thought?”

“I liked it. But, I guess I was wondering—what happened?”

“To who?”

“To you. You were a psychologist, right? Like hard-core? You worked at this institute, you studied my mom, and now you’re, like, a writer? What happened?”

I told her the official version. That well after the end of my fellowship and his marriage, Benjamin and I had started, tenuously, appropriately, dating. That I’d joined him in Paris on his sabbatical, where I’d fallen in love with both Benjamin and Augustine, accidentally begun a book, accidentally begun a marriage. It was true, if not the whole truth. Alice didn’t need to hear the ways that her mother’s case had tainted the field for me, the ways that loving Benjamin eventually foreclosed the ambitions that had brought us together. Once Benjamin and I went public, a job offer or even a recommendation would have been suspect. Not that it hadn’t been done before; it was ignoble tradition, marrying your professor, leveraging love into career advancement. But I wasn’t willing. I couldn’t work for him and I refused to leave him. So I’d expanded my horizons—that was how I liked to think of it. Loving him had made my world bigger. I’d found something new to love.

“So how come you never wrote another one?” she said.

“I’m working on a project as we speak. Nonfiction is slow.”

“I mean, yeah, but it’s been, like, a decade. And it’s not like you have kids or anything, so…”

It was true, I didn’t have, like, anything. It was technically not true that I’d never written another one. My name was on the cover of the coffee table edition of Augustine photos they’d brought out a couple of years after publication. There were interviews and essays, requests to write a review or a foreword, the introduction to the anniversary edition, the year wasted consulting on a PBS documentary that never aired. There was Benjamin, his fund-raising functions, his travel schedule, his distaste for any archival research that would put too much distance between us. There was the project I’d set aside in favor of the book about him. There was the book about him, which I could not bring myself to want to write.

“Did you ever want them? Kids?” she asked.

“We had Nina,” I said, as I’d been saying in response to this question for almost two decades. “Benjamin’s daughter.” I had assumed, at the beginning, that we would. My mother had warned me: his child would be my child, and the idea had both terrified and enticed. I thought I’d found a loophole, motherhood without mother or daughter. It became clear, by legal dictate and Nina’s desire, that I would be no kind of mother at all. It took longer to understand this was how Benjamin preferred it.

“You never wanted kids of your own?”

It wasn’t accurate to say I never wanted to, any more than it would be to say I wanted not to. I wanted Benjamin; Benjamin wanted no more children; I stopped asking myself whether I wanted at all. “No.”

“Do you regret it, now that he’s…?”

“Why, because then there’d be some evidence of my marriage?”

I must have said it more sharply than I’d intended, because her answer sounded like an apology. “I just thought it might be less lonely?”

I had a career, I told her. I had friends. A house to care for, books to read, health to maintain.

I didn’t tell Alice how little it all added up to. How much time there was to fill. Women my age were supposed to crave more time for themselves. This was an evergreen topic of lunch conversation and the infinite email chains of schedule juggling required to get us there in the first place. Women my age were leaning in, having it all or accepting they could not. They were waging small rebellions in the form of aromatherapy and candlelight yoga, Facebooked self-care whose prime purpose seemed to be the advertisement of how much time they spent caring for everyone else. I was meant to be performatively overwhelmed, defined by obligation to others. Instead, I was untethered, obligated to no one but myself. I liked to tell myself that this was triumph over the patriarchy, but mostly it seemed evidence that I was useless. No one would be inconvenienced if I disappeared from my own life.

“I’m alone,” I told Alice. “Not lonely. You might be too young to know the difference.”

“You think my dad’s lonely?”

“Maybe,” I said. “Probably. It’s all so fresh.”

“Yeah.”

I was reminded the wound was fresh for her, too, no matter how hard she was trying to pretend otherwise. “Does he know you’re here?”

She nodded. “It’s our family rule, total honesty.” A wry smile then. “Until recently, I guess.”

“What does he think about it? You coming here, asking all these questions.”

“Hates it.” She laughed. “You’d think I told him I was going to Syria or something. I don’t get what he’s so worried about. And I really don’t get why he’s not just as curious. Like, how do you spend all these years not wanting to know what happened? Especially now? I don’t get it.”

“Maybe he’s afraid of what he might find out.”

“Like what?”

“Like anything that doesn’t line up with the person he remembers. When someone’s gone, that’s all you have left.”

“You say gone like you mean dead. It’s just as likely she’s missing. Right?”

I couldn’t tell whether she really believed it. I tried to, for both of them: a new Wendy, off the grid, a hammock in Bali or a beach in Mexico or a cardboard box in a dark alley, making a different life. “But your father doesn’t believe that, right? He thinks he’s grieving his wife.”

Her shoulders slumped, almost imperceptibly.

“If you think someone’s not coming back, you don’t want to find something out about them that you can’t un-know.”

* * *

After dinner I shut myself in our bedroom, put on Bach’s The Art of Fugue, closed my eyes, let sound carry me backward in time in a way that no visual cue ever could. If aphantasia was a kind of mental blindness, I wondered if the analogy held, and other mental senses were consequentially heightened. I could summon the Bach melodies in my head at will, and almost persuade myself I was listening with Benjamin; I could almost, when I concentrated, conjure his arms around me, our hearts beating metronomically with the notes. Actual listening was harder on the heart.

Benjamin said the fugue was like the self: fugal subjects inverting, subverting, transforming o

ver time, but always, somehow, ineffably and fundamentally the same. He said the fugue was like the mind, rigid rules imposed on finite elements spawning an infinity of combinatorial possibility, a generative complexity from which arose thought, beauty, human consciousness. He said the fugue was a junction of reason and unreason, enlightenment rationalism fused with renaissance mysticism, a liminal space where finite met infinite. He said Bach used music to encode the divine—like our neurons, Benjamin said, our axons and dendrites, our neurotransmitters, every mind its own creator. He did not say that the music made him a child again, helped him remember how to love his father, for whom Bach had been the only tolerable talisman of a lost history. He did not, as a general and ungently imposed rule, say much of anything about his father or what had happened after his father’s suicide, Sacher torte, schnitzel, and cold Viennese gentility replaced with kugel and borscht and the aggressive Russian warmth of his mother’s extended family determined to smother the fatherless boy. He did not say that Bach was beyond his mother’s grasp, but I could tell he thought it, and never advanced my own theory, that the music was as much about trying to understand his mother as it was trying to recapitulate his father—that the idea of life as an infinite permutation of finite rule, faith encoded in law and law the pathway to faith, was embodied by his mother’s Judaism, all those rituals and prayers and kashrut silverware, everything he’d fled from into the arms of his self-described shiksa first wife. Even early on, I knew better than to say any of that.

I liked the canons better, music that turned in on itself with a finite trajectory. Melodies that played again and against until you couldn’t help but claim them as your own. The brain’s assembly of neural music processing centers is called the corticofugal network; we’re programmed to read repetition as love. Music as pattern recognition. Melody as the comfort of an old lover’s shirt. You could argue the pleasure of music has little to do with the music itself. The brain takes its pleasure from remembering. Even a bad memory, after enough time has passed, feels like home.

* * *

I couldn’t sleep. I found Alice on the living room couch watching my soap on my TV.

“You watch this?” I settled beside her without asking. It was my house. “I thought no one under the age of forty watched these anymore. Or no one, period.”

She shrugged. “I’ve seen it.”

At the commercial break, she declined to fast-forward the ads, instead asking if I’d been watching the show for a long time.

“My whole life, pretty much.”

“Did it always suck this much?”

“Not the way I remember it.” What I remembered: giving my Barbies riding lessons on toy horses while my grandmother guzzled tea and yelled at the screen. The bliss of winter vacations, blanketed beside Gwen, laying bets on how long it would take Jasper to kiss Olivia. Late nights in LA, Gwen up with the new baby, nursing, watching the week’s recorded episodes and describing the action to me, the phone and me huddled in my soon-to-be ex’s closet, whispering, hungry for updates because Lucas, predictably, refused to own a TV. Then later, after I’d moved back to Philly, Gwen still nursing, forever nursing, me playing hooky from the Meadowlark to keep company with her boredom, the two of us playing at kids on Christmas break, scarfing Doritos and Tastykakes, Gwen passed out and drooling on the carpet, baby Charlotte done same on my chest, tiny fingers sleep-clutching at my nipples like she could sense their fallow potential, her soft skin, soft breath, soft weight, the feeling, in that room, like Charlotte was part of Gwen and so also part of me. I remembered watching with Wendy.

The show came back on. A desiccated Jasper was trying to sweet-talk his on-again, off-again wife, Olivia (second, fourth, and fifth marriages), into forgiving him for kidnapping their child twenty-five years before. Jasper had given the baby up for a black market adoption, told then mistress Olivia it had died at birth, let the secret fester ever since—until now. I should tell Alice, I thought, that I watched the show with her mother.

“My best friend and I have been waiting half our lives for this secret to come out,” I said instead. It was still how I thought of Gwen, even now: best friend. Embarrassing, maybe, that this far into adulthood I still clung to a child’s concept of friendship—or maybe just embarrassing that I’d never made a new one.

“Satisfying?”

I’d only said it because I needed something to say, but realized: “Deeply.”

“You can go call her and celebrate, or whatever. I don’t mind.”

“Thanks for your permission.” It came out sharper than intended. “Sorry. I just… we’re not exactly on speaking terms.”

“Big fight?”

“Something like that.”

Once a cheater, Gwen had warned me for the last time, but by far not the first, when I asked her to witness the wedding. An intimate nonevent, I told her, city hall, just the two of us and our two witnesses. She reminded me I’d always been the girl who wanted the fairy-tale dress, flowers in my hair, was a sucker maybe not for the wedding-industrial complex, but wholeheartedly for the juvenile trappings of love. I’d also wanted a father to walk me down the aisle, give me away, dance with me to Ray Charles or the Everly Brothers, but I didn’t explain this to her, because I was tired of explaining things to her. She reminded me I hated Philadelphia, and even more hated the suburbs, but here I was planning to move into another woman’s house, mausoleum of her dead marriage. A man who marries a mistress creates a job opening, she said, then pretended it was a joke. You’re giving up your career for him, she said, not a joke. Look how well that worked out for his wife. Ex-wife, I said. I said a lot of things. As did she. I disinvited her from the wedding. Benjamin and I got married alone, witnessed by two strangers recruited from the courthouse lobby. I missed Gwen, until the memory of missing her overtook the memory of having her. Then there was nothing left to miss.

Alice paused the show. “So whose fault was it? Like, which one of you has to apologize?”

“It’s more complicated than that.”

“Huh.” Amazing how much judgment you could infuse into that sound.

Maybe Wendy Doe was dead after all, I thought, her spirit empowered to visit this girl’s presence on me. See how it feels, I imagined her saying, to have a witness. To be an object studied objectively, without mercy.

“My mom watched this show, too,” Alice said into the silence. “That’s why I do. Weird coincidence, huh.”

“It’s a popular show.”

“Or she remembered watching it with you. She did, right?”

I nodded, caught. Seen.

“Maybe she remembered everything, and just pretended not to.”

“Eighteen years is a long time to lie.”

“Yeah. It is.”

* * *

Just before dawn, I gave myself permission to check on Gwen’s Facebook page. This was a temptation I’d been indulging more and more since the funeral, which was the first time I’d seen her in more than a decade. She’d skipped my wedding, but showed up for the funeral. It felt like she was there to gloat. Per her prediction, the marriage hadn’t lasted.

To be clear: I knew why she was there. She’d come to express sympathy and care and maybe even apology or forgiveness, depending on which she believed was merited—and I knew this because I would have done the same. Knowing did not alter the feeling. I felt, on seeing her, too much rage and too much remembering, and that was a day I endured only by doing my best to feel nothing at all. So I kept my distance, and she kept hers. Afterward, she’d sent a card. Generic, a swan on the front, Hallmark conjuration of sadness. Inside, beneath the printed “sorry for your loss,” she’d written: I wish I knew what to say. Love, Gwen. I’d been unable to decipher its hidden meaning, whether this was her version of reaching out or an admission that she couldn’t be bothered. Maybe we were, in her mind, childhood friends who’d drifted apart in the natural way of things. It felt juvenile, stalking her on social media, obsessing over our past—the kind of thing peop

le with children, with living husbands, wouldn’t have the spare time to do.

Her Facebook page was all good fortune. The baby was in college. I’d held her while she sucked from a bottle; I’d dangled a rubber frog over her face while Gwen bathed her in the sink; I’d scrubbed her vomit off my shoulder, her shit off my jeans; I’d missed her entire life. She had her father’s stupid smile, but the rest of her face was all Gwen. Her prom dress was several inches too short.

Crashed

Crashed Girls on Fire

Girls on Fire Wish You Were Here, Liza

Wish You Were Here, Liza Game of Flames

Game of Flames Skinned

Skinned Wired

Wired Pride

Pride Hacking Harvard

Hacking Harvard The Waking Dark

The Waking Dark Lust

Lust Wrath

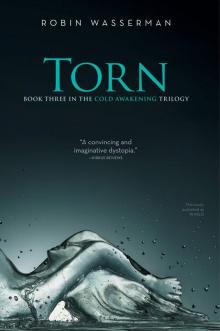

Wrath Torn

Torn Shattered

Shattered Sloth

Sloth The Book of Blood and Shadow

The Book of Blood and Shadow Mother Daughter Widow Wife

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse)) Wired (Skinned, Book 3)

Wired (Skinned, Book 3) Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins)

Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins) Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))