- Home

- Robin Wasserman

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Page 11

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Read online

Page 11

“Okay. And we know space and time to be fundamentally connected, each defining the other. A space-time continuum, as Einstein and Zemeckis would have it. So why assume discontinuity across spatial states but continuity across time? Why assume the Elizabeth of the present and the Elizabeth of the past are one rather than two? Or infinitely many?”

Benjamin called him my pet historian, and treated the friendship with the same indulgent condescension that, before publication, he’d treated my new “hobby.” It wasn’t his fault: I’d kept my work on the book away from him for as long as I could. I wanted, in those first few years, something that was mine. I didn’t want him to know how hard I was trying, in case—as seemed almost inevitable back then—I didn’t succeed. When I unexpectedly did, when suddenly there was a book, a sale, a career, it must have seemed to him like a happy accident, birthed without effort or intent, like a baby slip-sliding out of a prom queen who, until amniotic fluid seeped through silk, had failed to notice she was pregnant.

“I know there’s a me and a you because we have distinct consciousnesses,” I said. “And continuity of self across time may be an artifact of consciousness or its precondition, but either way, for the record, I bring everything back to the brain because that’s where everything goes.”

Sam grudgingly acknowledged the role of consciousness, but argued this, too, was based on unexamined assumptions, dependent on an unfounded faith in the collapse of quantum indeterminacy, and we debated the many minds theory, hidden variables, multiverses, and materialism until the coffee went cold and I’d managed to forget I was anything but pure consciousness myself.

* * *

Any duration is divisible into past and future The present occupies no space. So said the other Augustine, correctly. All good things must, et cetera, so coffee with Sam gave way to the Meadowlark, to Mariana. Every time I went back, more had changed. Mariana had occupied Benjamin’s office. She’d replaced his dark wood and leather furniture with modular space-age pieces, all synthetics and glass. The walls were pale blue; the oil paintings had been replaced by blown-up photographs of Golgi silver stains. His couch was gone. His armchair, his antique desk, his Moroccan rug: gone. There were no remaining surfaces that would have welcomed a body in heat, only sharp edges, slick plastic, too much light. It felt like the waiting room of a dermatology office. A physical erasure, as if he’d never been, as if this room had never witnessed our bodies in fusion, as if we had never been. I hated her, this woman who’d spent more minutes with my husband than I had. I wanted to tag every place I’d fucked him, every spot of floor bearing trace sweat and flesh.

We air-kissed.

“Let’s get down to it,” she said. “Busy day.” Mariana had rescheduled the interview three times. She never would have come right out and told me she didn’t think I should write the book. She simply slow-walked files, begged legal liabilities, and expressed an unprecedented concern for my welfare, taking on a project like this in the midst of my “difficulties.”

“Of course. The job must be overwhelming.”

“Nothing I can’t handle.”

She smiled, I smiled. Mariana had devoted her professional life to burnishing Benjamin’s reputation and carrying out his whims, and sold herself to the board as the ideal purveyor of his continuing legacy. A book like this would be catnip for donors, a free fund-raising tool she should have been begging me to write. But I’d known Mariana for nearly twenty years. She didn’t beg.

“Maybe you can walk me through how the institute has changed over the course of your tenure here,” I said.

“We’re taking some exciting steps toward synergy and team-based research. Until recently the Meadowlark has functioned with a bit of a rock-star mentality, but I truly believe that cooperation, rather than competition—”

“I didn’t mean your tenure as acting director.” I put the inflection where it belonged. “It seems best for everyone involved that the book doesn’t go into the institute’s decline.”

“Has it escaped your notice that I’m doing you a favor here?”

“You’re doing yourself a favor,” I said. “This book will be good for all of us.”

“You keep telling yourself that, Lizzie.”

Mariana was the only one at the Meadowlark who still called me that. It was a dog whistle, her covert reminder that I was still the same mangy stray who’d nosed up to the boss and nuzzled his hand till I got a treat. It said: I knew you when, and you turned out even worse than expected. The institute was her life, and she’d never stopped judging me for leaving it, and my “real” career, behind for a man. She thought I was one of those women, and in her presence, I felt like one.

I knew her when, too. The industrious worker in the Mickey Mouse sweatshirt whom Benjamin had diagnosed early on as lacking a necessary spark. I could have told her that he knew from the start she had no capacity for greatness, would never do significant work. She would simply be useful, he predicted, and she was.

“Why don’t we start with your first years here, and go from there.”

We slogged through the rest of the interview without incident, probably because I let my recorder do the listening for me. After twenty minutes, she made clear my time was up.

“I hope we’ll be seeing you again soon,” she said, insincerely enough that I couldn’t help telling her I’d be back later that week. It was such a pleasure to disappoint. “The daughter of a former subject wants to take a look around. I’m assuming that won’t be a problem?”

It was as delicate as it was infuriating to have to secure permission to enter the building I had, until recently, considered an extension of my home.

“Which subject?” Mariana asked. “And why didn’t she come straight to me?”

“Because it was my subject. Remember Wendy Doe?”

Mariana shook her head, her meaning clear—not no, she did not remember, but no way in hell. “What could that woman’s daughter possibly want with you after all this time?”

“Her mother’s… gone.” The circumstances were none of Mariana’s business. “The daughter’s curious. I’m trying to help.”

“Jesus, Lizzie. What’s she looking for? An excuse to sue us?”

“Of course not.”

“This woman’s daughter comes poking around, and you think she’s just, what, curious? Do I have to remind you the board is about to make its decision? Are you trying to give them a reason to pass me over?”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“Lizzie, the board is just looking for an excuse—I’m asking you as a personal favor, please don’t give them one.”

“I’m not your enemy, Mariana. When it comes to this place? I’m effectively no one.” As she couldn’t help reminding me.

“Just tread carefully.”

“Always.”

We stood, gave each other the obligatory drive-by cheek kiss.

“I miss him, too, you know.” She meant she missed him better. She meant she got the best of him, this place his favorite child, this work his favorite wife.

“I know.”

ALICE

The Meadowlark wasn’t what Alice expected. She’d scanned its glossy website, but that was all sound bites and press releases, photos of shiny new brain-scanning machines. She’d assumed that in person, the institute would carry more scars from its past. The building had once housed an insane asylum—at least technically, the widow had explained, its concrete foundation and some of its architectural bones still left over from the bad old days of straitjackets and padded walls, and, yes, the widow admitted when pressed, there were still straitjackets and padded walls somewhere within the facility, but only for precautionary purposes. Still, Alice pictured her mother strapped to some stained gurney with probes stickered to her skull, burly nurse looming over with a wolfish grin. She’d always thought of herself as someone without an imagination, but like many of her beliefs, this one had recently given way.

She hadn’t expected the infamous Meadowlark Ins

titute to be so suburban, sandwiched between a gas station and a strip mall, just down the road from a discount shoe warehouse. The widow explained that 150 years before, this had all been farmland, considered a safe enough distance from civilization to house the nuts. The earliest patients had milked cows, fed chickens, hoed weeds, supposedly sweating out their madness a little more with each hard day’s work. Alice asked if this was why they called them funny farms. The widow didn’t know. From the outside, the building looked quaint, harmless. On the inside, it was every bit the state-of-the-art mecca for brain science its website had promised. Alice tried to focus: her mother had once lived here. Her mind refused to settle.

For months, she’d been obsessing about her mother’s time here—and now here she finally was, her mother all she should have been thinking about, but her traitorous mind had shifted gears. She was thinking about the night before. Reliving it. She was following the widow through the building where her mother had taken refuge, and all she could think about was the blood she’d blotted away when she woke up sometime before dawn and remembered she was supposed to have peed after. The rusty streaks on the sheets they’d both pretended not to notice. The silent SEPTA ride into the city, so he could go to work and she could train back out to the widow’s suburb. The relief of having survived her poor choices; the terror of consequence.

Here was the room that had belonged to her mother. It was unthinkably small. She tried to focus: her mother, here, alone, nobody. She lay down on the bed. Her mother, younger than her mother had ever been.

Her mind, though, was too full of a stranger’s hands, the strange wet of a stranger’s tongue in her ear. Her mind was too full of disease. Secretions. Minuscule openings through which disease could ooze. The tender, raw spot inside her left cheek where she’d gnawed the tissue white, where something of him could have gotten inside her.

She thought, forcibly: my mother was here.

She focused on the body. This is the ceiling my mother saw when she tried to sleep; this is the air my mother breathed when she tried to remember.

When Alice’s mother disappeared, she had been teaching her online students the unit on the octopus, which was her favorite. Alice always knew when she reached that lesson, because dinner became a forum for “fascinating” factoids about the geniuses of the sea. They think with their bodies, her mother would say, every year, as if for the first time. Each arm thinks for itself. If we weren’t so obsessed with the brain, she would say, then maybe we would see it was true of us, too, that we are as much our legs, our kidneys and fingers and heart. Alice wished now she had paid better attention, because it must have signified. Was her mother clinging to the hope of continuity between herself and Wendy Doe, that some trace of that other self was still embedded in her cells? Or did it comfort her to believe body and mind were inseparable, that if she rooted herself in flesh, distributed herself through circulatory and respiratory systems, through muscle and skin and bone, then next time, if there was a next time, she couldn’t be so easily dislodged from her carnal home?

“There’s no lock on this side of the door,” Alice said.

“No.”

“There’s a lock on the outside, though.”

“Well.”

“Did you lock her in?”

“We never wanted her to feel like a prisoner here.”

Alice imagined herself closed inside this room for one night, for two, and wondered how many nights it would take to internalize the lock, to spend the rest of her life looking for escape.

* * *

The widow stopped at the last door on the corridor but did not open it. “You shouldn’t expect too much.”

“You already said that.” Behind this door was the one person left at the Meadowlark who had been close to her mother. But he’d lived here for twenty-five years because he could not form new memories. He lived in an eternal present, and supposedly whatever he knew of Alice’s mother was lost in his irretrievable past. Alice wanted to meet him anyway.

“I just don’t want you to be disappointed.”

This door was locked. The widow punched in a combination, and they stepped inside. The subject, Anderson Miles, was seated at a piano, which was the strangest thing Alice had seen yet. He looked to be in his early sixties, bald with mottled skin and the sick gray of someone the sun had forgotten. He was staring at the piano keys, blank.

“Hello,” the widow said. “Would you like some company?”

This won them a smile of yellowing teeth. It occurred to Alice that if your life restarted every seven minutes, it would never seem incumbent to brush. “Everyone’s always welcome here.”

“I’m Lizzie.”

Alice glanced at the widow, surprised. She didn’t seem like much of a Lizzie.

“This is Alice. I think you knew her mother.”

“Nice to meet you, Alice. Does your mother look anything like you?”

Something like hope, fluttering. “Maybe? A little? Why, do I look familiar?”

“Oh, no. And I’d remember a face like yours, I’m certain of it.”

“Oh.”

“What was her name?”

Alice hesitated. “Wendy.” She’d started thinking of Wendy Doe the way the widow did—as if she were a real person rather than a symptom. “She lived here with you.”

“No, I don’t think so.”

Alice described her mother, and Anderson thought about it, his effort evident. She waited.

“Visitors!” he said after a moment. It was as if his expression had been smoothed out by an eraser. “How lovely.”

The widow had explained that hippocampal damage prevented new memories from rooting themselves into Anderson’s brain. Anything that had happened since he was thirty-two years old—including his doctors repeatedly explaining his condition, including his wife saying one last goodbye, including his mother dying—had, for him, not happened at all.

Alice tried again, introducing herself, describing her mother. Anderson shook his head. “I don’t think so, no woman’s ever lived here with me.”

“No, not here, not with you—” They went through another round, and another, more I don’t think so, more that doesn’t sound familiar, more I don’t remember, more there was no woman. It was frustrating at first, then enraging, that her mother’s existence could so easily be erased, but gradually Alice began to find the repetition soothing. It made sense that her mother would have taken comfort with this man, with whom you could make as many mistakes as you liked, trust in the inevitable baptism of erasure. It made sense that a woman prone to vicious forgetting might want to be forgotten.

As Elizabeth picked up the conversation, Alice let her mind wander—to the past she imagined for her mother, and the pasts she imagined coming before her, barefoot women in filthy nightgowns screaming at the walls. She indulged briefly her panic about the night before, decided to acquire a pregnancy test, just in case. She worried about her father, alone with his dutiful grief, and she worried about Daniel, who was wasting his time worrying about her. Then she let her mind stray to forbidden territory, wish fulfillment. Imagined her mother drawn back to this city, back to this place. Imagined her mother, memories and self buried deep in her damaged brain, wandering into this strange building and setting eyes on Alice. Love, recovery, reunion.

The fantasy broke open with the sound of the piano. Anderson played beautifully, fingers flying across keys, head bobbing with the flourish of a concert pianist. The shock wasn’t that he could play well, but that he was playing Bach’s “Unfinished Fugue.”

Time stopped.

This was her mother’s music. These were the chords of her childhood, of letting a Dorito go soggy in her mouth to avoid a crunch, because Mommy was anxious and only listening to Bach’s strange loops could soothe. These were the collapsing melodies her mother had taught her to follow. These were the notes she had picked out on the keyboard with her stubby young fingers, her mother clapping with the metronome, cheering her on.

He

r mother had been here. It was real, suddenly. Karen Clark, Wendy Doe, whoever she thought she was—she’d been here, with this man and his piano. The music ended midbar. Anderson gaped at his hands like he’d just discovered them. He started at the sight of Alice. “Oh, hello! What a pleasure.”

“The playing sustains him,” the widow said quietly. “When he focuses on the music, he can make it to eight minutes, sometimes nine. But it always ends.” Her face was shiny with tears. That was Alice’s pain. It was Alice who should have been able to cry.

She could not cry. This was her mother’s favorite piece, and it could not be coincidence. This was a melody of the Meadowlark—and it was confirmation that Alice had been right. Whatever happened to her mother here had left its mark. The music was proof. Something in her mother must have remembered.

ELIZABETH

I read about it first in the Times, which for Benjamin was a disqualifying factor. Newspapers didn’t break science, he would say. These days they barely break news. Still, we read the Times in bed on Sunday mornings, because this was the vision he’d had of marriage. Before the divorce, when he was still comparing his wife to me, rather than vice versa, he admitted that this was what he’d missed most: the quiet rustle of Sunday mornings. It’s all cereal and finger paint now, he would say, nibbling my ear, and don’t get me started on fucking cartoons. That wasn’t even the worst of it: on their daughter’s third birthday, his wife had proposed an idea. Take the daughter to church. Take my fucking daughter, my dead father’s only grandchild, to fucking church, Benjamin said. As if my father survived the attempted extermination of his people only to see me deliver my Jewish seed to Jesus, talk about a devious missionary program—and when I say missionary, he would say, meanly, I mean it in all possible connotations. I wish I could say I hated when he spoke like this about his wife.

Thus we spent each Sunday of our finger-paint-free matrimony swapping sections with ink-stained fingers. That day’s paper unveiled a newly coined neurological disorder, aphantasia, the inability to close one’s eyes and conjure up a visual image. Benjamin was underwhelmed by the research, but then, the more his habitat shifted from lab to cocktail party, the less he wanted the reminder that somewhere out there, lesser brains than his were producing better work. I told him that the research was beside the point, the point was that until encountering this article, it had never occurred to me this conjuring was magic anyone could do. Nine years of training in cognitive psychology, a seventeen-year marriage to a world expert in the workings of the mind, and it had never penetrated that the “mind’s eye” was anything but a useful metaphor. What if what you see as red is not what I see as red—no one who’d ever gotten stoned had escaped that revelation, but in all that late-night dorm-room philosophizing, it had never occurred to me that all those pretentiously stoned assholes could close their eyes and literally see red. Among the infinitude I could not evoke in my mind’s blind eye: A sphere. A sunset. My childhood house. My father’s face. A fire-breathing dragon. The photograph from our wedding day, just behind me on the nightstand. Benjamin loved it; we spent the rest of the day experimenting. Can you see this? Can you see that? When you say see, how do you mean it? How do you draw, how do you write, how do you dream? How do you fantasize yourself into orgasm? How do you miss me when I’m gone? It was a time warp of a day, both of us slipping joyously back into our younger selves. Then we had takeout for dinner, then we had predictable sex, then he took his various medications and I tried sporadically to sleep, and the next day was the same as any other, and I didn’t think about it again.

Crashed

Crashed Girls on Fire

Girls on Fire Wish You Were Here, Liza

Wish You Were Here, Liza Game of Flames

Game of Flames Skinned

Skinned Wired

Wired Pride

Pride Hacking Harvard

Hacking Harvard The Waking Dark

The Waking Dark Lust

Lust Wrath

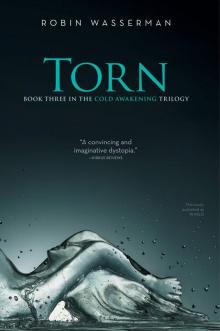

Wrath Torn

Torn Shattered

Shattered Sloth

Sloth The Book of Blood and Shadow

The Book of Blood and Shadow Mother Daughter Widow Wife

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse)) Wired (Skinned, Book 3)

Wired (Skinned, Book 3) Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins)

Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins) Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))