- Home

- Robin Wasserman

Hacking Harvard Page 2

Hacking Harvard Read online

Page 2

Two days before, a bewildered freshman, still learning her way around the hallowed labyrinthine halls, had foolishly asked an upperclassman for directions to room 131. She'd ended up in the second-floor boys' bathroom. Ten minutes later she'd slipped into history class, face red, lower lip trembling, sweat stains spreading under either arm. She hadn't gotten two words out before Ambruster had ripped into her, threatening to throw her out of his room--out of the school--for her blatant disregard for him, his class, his time, his wisdom, and the strictures of civil society. As she burst into tears, he shoved the pink slip in her face and turned away.

15

And for this, Eric had decided, Dr. Evil needed to pay.

The freshman was blond, with an Angelina Jolie pout. . . and eyes that seemed to promise misty gratitude--so Max was in.

Schwarz didn't get a vote, and didn't need one. He just came along for the ride.

In the morning, Ambruster's howl of rage would echo through the halls of Wadsworth High School, and Eric would allow himself a small, proud smile, even though no one would ever discover the truth about who was responsible. In the morning, Max would try to scoop up his willing freshman and claim his reward, only to get shot down yet again. In the morning, Schwarz would wake up in his Harvard dorm room, which, two weeks into freshman year, still felt like a strange, half-empty cell, and wish it was still the middle of the night and he was still up on the roof with his best friends. Because that was the moment that counted. Not the morning after, not the consequences, not the motives, but the act itself. The challenge. The hack.

The mission: accomplished.

So what was I doing while they were scaling walls and freezing their asses off for the sake of truth, justice, and bleached-blond high school freshmen?

I was raising my hand, I was doing my homework, I was bulking up my resume, I was conjugating French verbs, chairing yearbook meetings, poring through Princeton Review prep books, planning bake sales, tutoring the underprivileged, memorizing WWII battlefields and laws of derivation and integration, exceeding expectations, sucking up, boiling the midnight oil, rubbing my brown nose against the grindstone. I was following the rules.

16

As a matter of policy, I did everything I was supposed to do. And as far as I was concerned, I was supposed to be valedictorian.

Except I wasn't.

At least, not according to the Southern Cambridge School District. Not when Katie Gibsons GPA was . 09 higher than mine by day one of senior year. All because in ninth grade, when the rest of us were forced to take art--non-honors, non-AP, non-weighted, a cannonball around the ankle of my GPA--Katie's parents wrote a note claiming she was allergic to acrylic paint.

I got an A in art.

Katie got study hall.

My parents threatened to sue.

And, only once, on the way into the cafeteria, because I couldn't stop myself:

Me: "Is it even possible to be allergic to acrylic paint?"

Katie: "Is it even possible for you to mind your own business?"

Me: "look, I'm not saying you lied, but ..."

Katie: "And I'm not saying you're a bitch, but. . ."

Me: "What's your problem?"

Katie: [ Walks away]

By the second week of senior year, the truth had sunk in. I wasn't going to be the Wadsworth High valedictorian. Salutatorian, sure. Number two. Still gets to give a speech at graduation. Still gets a special seat and an extra tassel. Probably even a certificate.

But still number two. Which is just a prettier way of saying not number one. Not a winner.

Then, in late November, something, somewhere beeped. A red flag on Katie's record, an asterisk next to the entry for her tenth-grade health

17

class, indicating a requirement left unfulfilled, a credit gone missing. She could make up the class, cleanse her record, still graduate--but not in time for the official valedictorian selection. She was out.

I was in.

The rumor went around that I'd given the vice principal a blow job.

Eric held out his hand, palm facing up. "Give it."

"What?" Max's beatific smile didn't come equipped with a golden halo, but it was implied.

"Whatever you've got in your pocket," Eric said. "Whatever you took out of Ambruster's desk."

"What makes you think I--"

"Excuse me?" Schwarz said, his voice quaking. "Can we get down off the roof now?"

"You can go," Eric said. "But he's not leaving until he puts it back."

Schwarz stayed.

Max rolled his eyes. "You're crazy."

"You're predictable."

"Clocks ticking," Max said, tapping his watch. "If the guard shows up after all and catches us here ..."

"It'd be a shame. But I'm not leaving until you put it back." Eric stepped in front of the elaborate pulley system they'd rigged to lower themselves to the ground. "And you're not either."

"You wouldn't risk it."

"Try me. Schwarz's skittery breathing turned into a wheeze. "I am sorry to interrupt, but I really do not think we should--"

18

"Schwarz!" they snapped in chorus. He shut up.

Max stared at Eric. Eric stared back.

And after a long minute of silence, Max broke.

"Fine." It wasn't a word so much as a full-body sigh, his entire body shivering with disgruntled surrender. He pulled a folded-up piece of paper out of his pocket.

"Next week's test questions?" Eric guessed.

Max grunted. "And the password to his grading database. You know how much I could make off this?"

"Do I care?"

Max sighed again and began folding and unfolding the sheet of paper. "So how'd you know?"

"I know you" Eric said.

"And just this once, couldn't we . . ."

Eric shook his head. "Put it back where you got it."

"You're a sick, sick man, Eric," Max said. "You want to know why?"

"Let me think . . . no."

"It's this moralistic right/wrong bullshit. It's like you're infected. Don't do this, don't do that. Thou shalt not steal the test answers. Thou shalt not sell thine term papers and make a shitload. Thou shalt not do anything. It's a freaking disease."

Eric had heard the speech before, and he finally had his comeback ready. "Oh yeah? I hope it's not an STD, or I might have given it to your mother last night."

Schwarz snorted back a laugh, and Max, groaning, shook his head in disgust. "First of all, I think the term you're looking for is yo mama," he said. "Second of all. . ." He pulled out his cell phone and

19

pretended to take a call. "It's Comedy Central. They say don't quit your day job."

"Put the test answers back, Max."

Max glared at Eric, but slid the paper back into Ambruster's desk. "If you'd just get over it, we'd be rich by now."

"If I didn't say no once in a while, we'd be in prison by now."

"Excuse me?" Schwarz began again, timidly.

Once again, the answer came back angry and in unison. "What?"

Schwarz spread his arms to encompass their masterpiece, the orderly silhouettes of desk after desk, the inspirational posters blowing in the wind. "It is beautiful, isn't it?"

It was.

Three proud smiles. Three quiet sighs. And one silent look exchanged among them, confirming that they all agreed: Whatever the risk, whatever their motives, whatever the consequences, this moment was worth it.

"Now can we please get off the roof?" Schwarz led the way down, holding his breath until his feet brushed grass. And a moment later, the three of them disappeared into the night.

It was their final dry run, their final game in the minor leagues. Max was the only one who knew it, because Max already had the plan crawling through his mind, the idea he couldn't let go. He hadn't said anything yet, but he would, soon--because up on that roof he decided it was time. The hack on Dr. Evil had gone so effortlessly, with almost a hint of bored

om. It was child's play, and Max was getting tired of toys.

He knew the idea was worthy.

He knew the plan was ready--and so were they.

20

I wasn't there, of course. But I've pieced it together, tried to sift the truth from the lies, eliminate the contradictions. And I've tried to be a faithful reporter of the facts, even the ones that don't make me look very good.

Maybe even especially those.

The three of them agreed not to broadcast what they'd done. But much as I know now, close as I've gotten to the center of things, I'm still not one of them, not really. And that means that I never agreed to anything. I'm not bound. I can do what I want--and I want to speak.

So like I say, this isn't my story to tell, but it's the one I've got. And all it's got is me.

21

22

October 7 THE BET

October 15 CAMPUS VISIT

October 19 SATs

November 17 THE GAME

November-December THE APPLICATION

December 31 APPLICATION DEADLINE/NEW YEAR'S EVE

February 3 THE INTERVIEW

March 10 ADMISSIONS COMMITTEE DELIBERATIONS

March 15 DECISION)-DAY

23

:,

24

October 7 THE BET

Objective: Agree on terms, select an applicant

October 15 CAMPUS VISIT

Objective: Preliminary reconnaissance

25

1

If you were going to hint plausibly that any American college is a sex

haven, you'd hint that it's Harvard. --Nicholas B. Lemann 76, "What Harvard Means: 30 Theories to Help You Understand," The Harvard Crimson, September 1,1975

I t's not a living wage if it means you're stuck living in a box!" Eric yelled, slamming the latest issue of Mother Jones down on the kitchen table. His father didn't even look up.

"The term living wage is a false construct," he said mildly, turning the page of his Economist. "Part of the delusion that income is somehow owed, rather than earned."

"You don't think the guy who empties your office trash can every night has earned the right to health insurance and food for his family?"

His father still didn't look up. "Don't exaggerate. It's sloppy."

Eric sighed, his mind still foggy from the previous night's rooftop adventure. It wasn't a good morning for an argument, even one he'd had a hundred times before. Even one he'd started himself. "It's not fair. They should--"

26

"It's not a question of fair, it's a question of what the market will support," his father snapped. "I thought I taught you that much, at least, before you abandoned the discipline to play with your toys. Maybe you need to reread your Adam Smith."

Toys. That's what his father called the gears and wires that lay strewn across Eric's room, the devices--alarm clocks, batteries, telescopes, then later, Wi-Fi--capable walkie-talkies and pencil-size image scanners--that Eric used to show off, before he knew better. As far as his father was concerned, engineering was a game. Whereas economics, according to Howard Roth, Harvard University's Ellory Taft Memorial Professor of Economics, was a discipline. Eric's father had never gotten over the fact that his prodigy son, who used to sit in the back of the grand lecture hall doodling supply and demand curves on the pages of his Rugrats coloring book, had moved on to what Professor Roth insisted on calling "playtoys" and so Eric, in return, pointedly referred to as "real science."

There had been a time when Eric had dreamed of attending Harvard, studying under his father, creating a Roth family economics dynasty . . . but then, there had also been a time when Howard Roth insisted on biking to campus, when his sweaters were hand-knit by his wife, when family dinners spurned meat in support of the rain forest, grapes in support of mistreated migrant workers, and, for a brief period, pork in support of the good karma Howard Roth believed he might accrue from the local rabbi and, on the off chance he was paying attention, God. Now Professor Roth drove the five miles to campus every day in a Lexus SUV, preferred Armani to Brooks Brothers, though he would wear Hugo Boss in a pinch, and ate whatever was put in front of him at his latest Republican fund-raiser.

Times changed.

27

"Maybe you need to reread Adam Smith," Eric argued, "because you don't know what you're talking about."

That made his father look up from his journal. "Remind me. Which one of us is the architect of the current national economic policy? And which of us hasn't been to a lecture on the subject since he threw a temper tantrum at age nine?"

Eric had plenty to say on the subject of the current national economic policy, and his father's architectural skills, which had proven about as effective in Washington as they had two years before, when he'd tried to replace a loose gutter and ended up punching a three-foot-wide hole in the roof. But his cell phone rang with a message from Schwarz.

911

Saved by the Battlestar Galactica--themed ringtone.

"I'm out of here." Eric jumped up from the table, grabbing a slice of bacon to go.

"Wearing that!" Howard Roth looked pointedly at the message running across his son's T-shirt.

NICE HUMMER.

IT LOOKS GOOD WITH YOUR TINY PENIS.

"They let you go to school like that?"

"It's Saturday," Eric pointed out.

"You should change."

"So should you," Eric muttered. But only once he was already out the door.

Eric burst out of the Harvard Square T station, ran through the Yard, and slipped into Stoughton Hall using one of the spare entry

28

cards that Schwarz had manufactured for his friends. There was no sign of a crisis. And when Max opened the door to room 19, he was beaming.

"So what's the big emergency?" Eric asked.

Max just swept him into the room, his smile growing wider. "You're not going to believe this one."

Schwarz was sitting at the head of his extra-long twin mattress, pressed up flat against the wall, his face pale and ashy, his eyes twitching behind his oversize glasses. He looked like a little kid convinced that there were monsters under his bed, and Eric had to remind himself, yet again, that Schwarz was a college freshman.

A sixteen-year-old freshman who had been homeschooled by his mother for the past two years and had yet to start shaving, but a college man nonetheless.

"Tell him what's going on, Professor," Max said, flicking something across the room. It was pink, and it spiraled as it flew, slapping down squarely on Schwarz's upturned face. It was a bra.

Schwarz squeaked.

"Get it off!" He gave his whole body a mighty shake, but the bra caught in his thick cloud of tight curls and hung there like an oversize earring, flopping back and forth as he shook his head so violently, his glasses flew off. "Please!"

Max ignored him and sank to the floor, convulsing with laughter. So Eric grabbed the bra, gave it a sharp yank, and pulled it off of Schwarz, who shuddered. If only the girls at Wadsworth High could see him now, Eric thought, suppressing a smile. Poor Schwarz, who hadn't even shown his face in Wadsworth's hallowed halls in the past two years, had accrued quite the reputation as a sex maniac, his punish

29

ment for the alleged sin of installing a micro camera in the girls' locker room. No one had believed that Schwarz built the camera for the purest of purposes--to see if he could--and was only persuaded to give it away to the actual Peeping Toms (three lying morons from the lacrosse team) because, well, it was impossibly easy to convince Schwarz to do anything.

No one knew that Schwarz had been nodding along to Max and Eric's wild schemes since he was a precocious six-year-old with a Star Trek fetish and the ability to recite pi to the 77th digit--in bases one through twelve. They didn't know that he believed it impolite and inadvisable not to say yes to pretty much everyone and everything-- and thus would give his camera away to his new lacrosse buddies just as easily as he would, and had, agreed to help

Max and Eric slime their second-grade after-school gifted counselor or rewire their fourth-grade teacher's phone to receive all--and only--incoming calls to the local twenty-four-hour psychic hotline. They didn't know Schwarz, and so they didn't realize that the five-foot-tall genius who'd skipped two grades and probably should have skipped two more, the one with the Playboy collection lovingly categorized and laminated in the back of his closet, avoided the beach every summer because, though he would never have admitted it, real live girls in real live bikinis freaked him out.

They didn't know Schwarz, and so they didn't ask questions, they just found the camera, believed the lying lacrosse morons, and called his mother in to the principal's office, and within a week Schwarz was spending his days poring through international topology journals on his own time, at his own alarming pace, in the security of his own home, while Elaine Schwarzbaum hovered and fussed, wondering how

30

to cure her son of his supposedly perverted proclivities, and Carl Schwarzbaum, when he remembered to stop by for a visit, winked at his son for a job well done.

If they could see him now, cowering from a bra ...

Not that Eric could completely blame him. The bra--and all it implied, the secret power it seemed designed to amplify and contain-- was an intimidating thing. Eric had seen bras before, but only his sister's and his mother's. And that didn't count. He turned it over in his hands. Pink, sort of satiny, with an almost fuzzy lining and a collection of snaps and clasps that looked like they belonged on a medieval corset, and the tiny flower in the center was--

Crashed

Crashed Girls on Fire

Girls on Fire Wish You Were Here, Liza

Wish You Were Here, Liza Game of Flames

Game of Flames Skinned

Skinned Wired

Wired Pride

Pride Hacking Harvard

Hacking Harvard The Waking Dark

The Waking Dark Lust

Lust Wrath

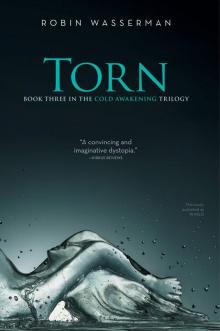

Wrath Torn

Torn Shattered

Shattered Sloth

Sloth The Book of Blood and Shadow

The Book of Blood and Shadow Mother Daughter Widow Wife

Mother Daughter Widow Wife Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Sloth (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse)) Wired (Skinned, Book 3)

Wired (Skinned, Book 3) Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins)

Gluttony (Seven Deadly Sins) Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))

Wrath (Seven Deadly Sins (Simon Pulse))